SJW: Hi Lilly! First off, thank you for being part of the Undead Darlings broadside series—you shared both your words and a piece of your father’s art that were left out of the published version of Negative Space—what a double-cool thing unique to this edition. Being able to consider the work of two artists in one print—talk about serious responsibility!

On responsibility: You’ve said that Negative Space is an archive as much as it’s a memoir, and that the exact representation of your father’s art in your book was essential to that project. I love that; I like to think of Undead Darlings as an archival project also, and the broadside series in particular as a way to glimpse some of what authors leave behind while writing and publishing a book. It’s a part of the process every writer knows so well, but one that is rarely shared with readers. I take that responsibility seriously; and I know you do too after reading your book and working on this edition with you.

Archives require curation, and curation requires difficult decisions. How did you manage the limitations for what art you could include in Negative Space? How did you make the hard decisions for what would be included—and what would be left out?

LD: Thanks so much for including me in this series! I really love the print you made.

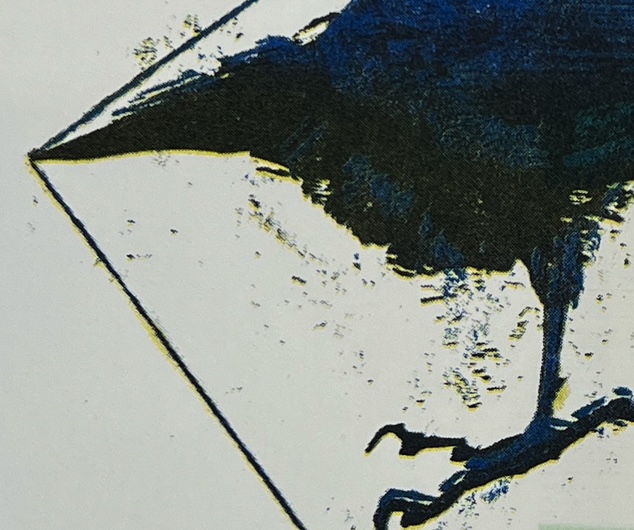

A lot of the decisions about which images to include in/leave out of Negative Space were made for me by logistical constraints. One big one was the fact that we were limited to black and white, which I resisted at first but didn’t mind too much in the end—so many of my father’s pieces are black ink on white (or off-white) paper, so those weren’t impacted by a lack of color, and without the color of the wood in the carved pieces, the texture is emphasized even more. But that constraint did lead me to remove several of the more colorful pieces that I would’ve included otherwise, including the black and blue bird that we ended up using for this broadside.

Another logistical constraint was the fact that I took all of the photos of the sculptures myself, with no photography background. I bought lighting equipment and asked a family friend to give me a crash course on how to use it, and the rest was all trial and error. If the work had all been located in one place, I might have hired a professional to photograph it, but since it’s scattered all over the country, that just wasn’t doable. And ultimately, I knew my father would have wanted me to push myself and figure out how to do it on my own. That was his ethos about pretty much everything, but especially opportunities to learn a new artistic medium. So I felt good about the choice to take the photos myself, but my inexperience meant that they didn’t all come out great, which weeded out several pieces.

Between those two constraints—plus the fact that so much of my father’s work has been lost to time, discarded, deteriorated, or sold without records—I didn’t have to make quite as many hard choices as I would have had his whole body of work been available to include. The choices were hardest in cases where there were two or three very similar prints, and I had to pick which one to use. I knew without a doubt that he would have had opinions about which ones were the best, but I couldn’t always guess what his selections would have been. So I had to give myself permission to choose the ones that I liked best, and remember that he valued my opinion and actually probably would have been delighted to see which pieces I chose, even if they were different from the ones he would have.

SJW: Early in Negative Space you write about the notes your father wrote in the margin of one of his books, responding to the idea that the written sentence can unburden someone of emotional trauma by translating the experience into signs, relieving them of its metaphorical “heaviness.” He writes: “and sculpture? who’s (sic) business is the ‘heaviness of things’?”

You conclude with this: “he was arguing in the marginalia that sculpture can turn life to symbols too, but uses heaviness to do it rather than resisting the heaviness of human existence—capturing our experiences and thoughts and emotions, bringing them down to the solid earth like a wild bird in a cage.” The way you write this thinking out—your imperative as a daughter, a writer, and an archivist—it’s just so on point. If there’s more personal and lyrical art criticism out there, show me!

I like to think that your father’s print of the bird that you shared for Undead Darlings is that “solid bird in a cage”—the action that carved lines and heavy ink create, the black and deep blue, the bold, angular border that follows its form. It’s gorgeous and alive on the page.

Yet, as you write in the passage you share for this edition, the fate of a material object is that it will inevitably succumb to the cracks and crumbles, scratches and scuffs of time “until there is nothing tangible left.” I feel that heaviness.

Do you think an archive—like your book—can transcend that fate? Or at least preserve the stories those objects have to tell? (I’m starting to think that every archive should have a memoirist there to work on it.)

LD: That’s the hope. Preserving and sharing the work itself, as well as the life and stories behind it, was my original motivation for writing Negative Space, and that remained really central to the project even as it evolved from a more straight-forward art book to its final hybrid memoir form. Books don’t necessarily last forever either, of course, but they can be reprinted. The book has the potential to last a lot longer than some of the most fragile pieces—and in doing so, preserve those pieces beyond what I’m able to do with the actual physical objects. And in addition to preservation, the book is a way to share the work. A lot of my father’s artwork lives in my apartment, where I enjoy it every day—and in my mother’s apartment, and my father’s friends’—but seeing people who never knew him engage with his work is like keeping a part of him alive.

“I like to think that your father’s print of the bird that you shared for Undead Darlings is that “solid bird in a cage—”

SJW: Now that Negative Space has been in the world for a year, I’m curious if you feel the urge to reveal other stories about your father and his artwork.

While working on this edition with you, I learned that you designed an exhibition of some of his work for the Negative Space launch event. That is such a rad way to launch a book–and no doubt the perfect way to celebrate this book. I wish I had been there for it!

If you were to design another show that featured your father’s artwork, how might it be different from what you put together for the Negative Space launch event? How would you design that show—what choices would you like to make–and what story might it tell?

LD: I don’t think I will do another show, honestly. At least anytime soon. Maybe in 20 years if the book has really made a mark and there’s a demand for it! Or, you know, if the Whitney comes calling (a girl can dream). But putting on the show for the launch was a very satisfying culmination of the work of the book. I spent over ten years inhabiting and writing my father’s story, engaging deeply with his work to describe it and use it as an entryway into the larger story of our family, photographing and preserving and sharing his work… I’m ready to move on to other projects, and I feel like I’ve done my duty as the steward of my father’s body of work. There’s now a book that anyone can buy, full of images of his work and the stories behind those images and all of my deepest thoughts about them, and that feels huge. I did that for both of us. And bringing people into a space where they could engage with the work directly, making the launch party for Negative Space a celebration of both my work and his, and this collaboration between us, was really everything I ever wanted for this endeavor. That was when it felt real and complete, even more so than the first time I held the finished book in my hands.

SJW: If you had to choose one artifact from your time writing Negative Space whose “business is the heaviness” of bringing that book to the world, what would it be?

LD: This is such an interesting question, and I’m not really sure. In a way, all of my father’s work that’s displayed in my apartment plays that role. I got to know each piece so much more intimately through the writing of Negative Space; it transformed and deepened my relationship with the work, and that shift is still palpable to me when I see pieces that I wrote about, that I’ve always loved but didn’t used to know quite as well. I did recently hang the original print that we used for the book cover on my office wall, as a kind of symbol, so maybe that’s my answer.

I also thought the whole time I was writing the book that I’d get a tattoo once it was published—I considered a few images but kept coming back the horseshoe crab pins, since they were things my father gave to his friends, symbols of being someone important to him. And he always wore one. I have one of the original pins but I’m afraid to wear it because I would be devastated if it got lost, so a tattooed version felt like a good solution. But once the book was out, I felt less of a need to commemorate it. The book itself is the commemoration, and the ongoing experience, all at once. It’s the heavy thing that allows me to live lighter.